Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Origins of Mind : 10

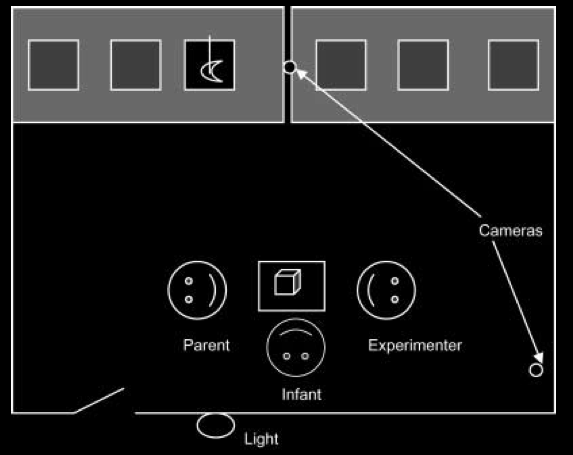

Liszkowski et al 2004, figure 2

why?

Why do infants point?

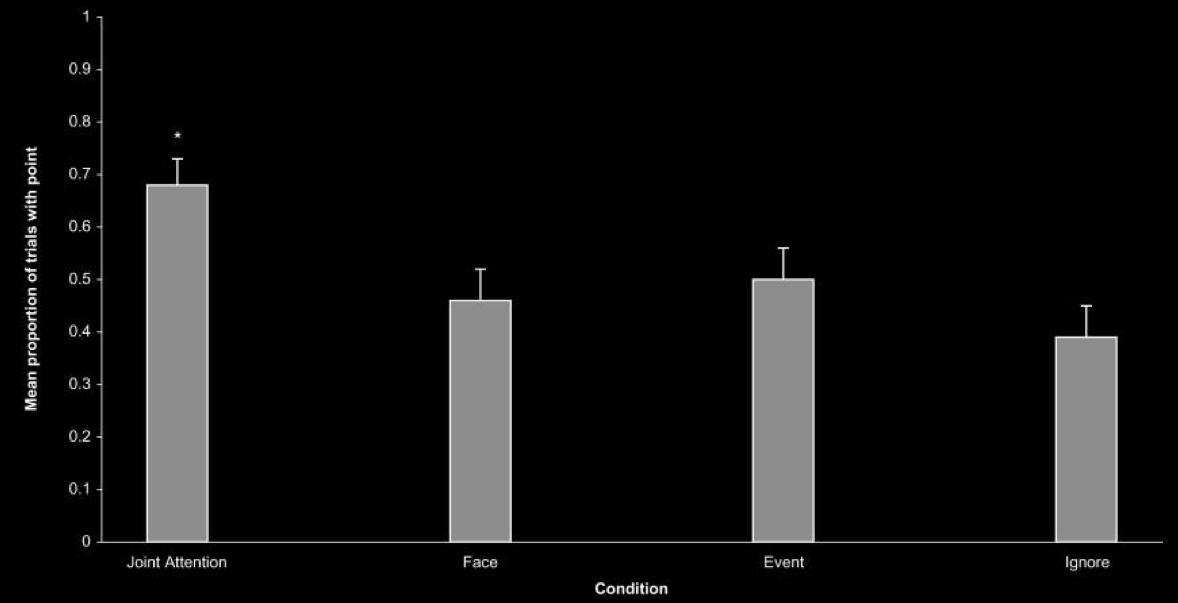

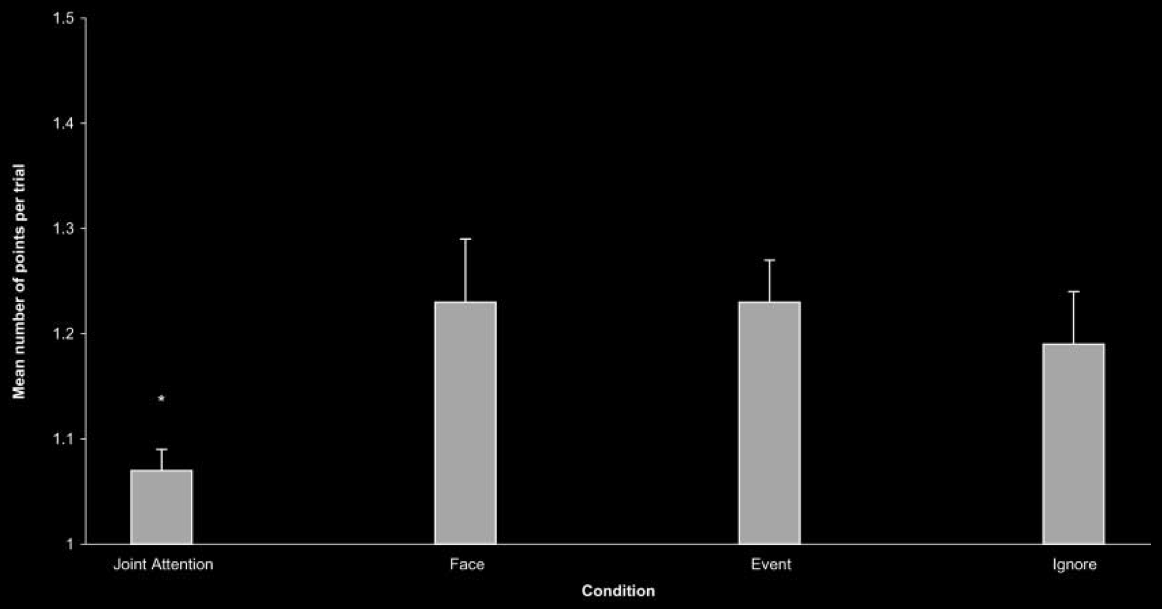

Liszkowski’s idea: find out by seeing what satisfies them.

hypotheses:

- for themselves

(prediction: ignoring them makes no difference)

-

to draw attention to themselves

(prediction: looking at them is sufficient to satisfy them)

-

to direct attention only

(prediction: looking at the referent is sufficient)

-

to initiate joint engagement

(prediction: looking at them and the reference is sufficient)

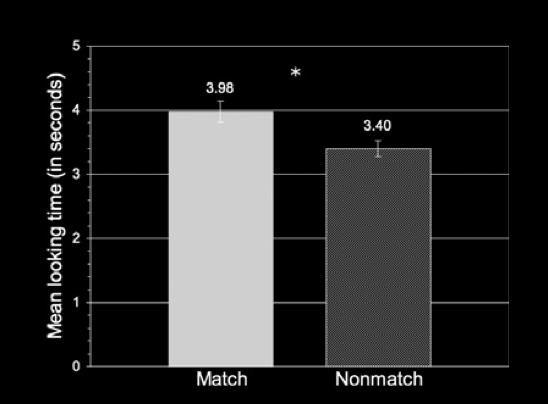

Liszkowski et al 2004, figure 1

Liszkowski et al 2004, figure 3

Liszkowski et al 2004, figure 4

12-month-old infants point not only to request but also to initiate joint engagement.

(And to inform.)

Pointing: Reference and Context

From around 11 or 12 months of age, humans spontaneously use pointing to ...

- request

- inform

- initiate joint engagement (‘Wow! That!’)

How do infants understand pointing actions?

Hypothesis 1: Pure use (compare block & slab).

‘Let us imagine a language for which the description given by Augustine is right. [...]

A is building with building-stones: there are blocks, pillars, slabs and beams.

B has to pass the stones, and that in the order in which A needs them.

For this purpose they use a language consisting of the words ‘block’, ‘pillar’, ‘slab’, ‘beam’.

A calls them out; B brings the stone which he has learnt to bring at such-and-such a call.’

Wittgenstein (1953, §2)

How do infants understand pointing actions?

Hypothesis 1: Pure use (compare block & slab).

From around 11 or 12 months of age, humans spontaneously use pointing to ...

- request

- inform

- initiate joint engagement (‘Wow! That!’)

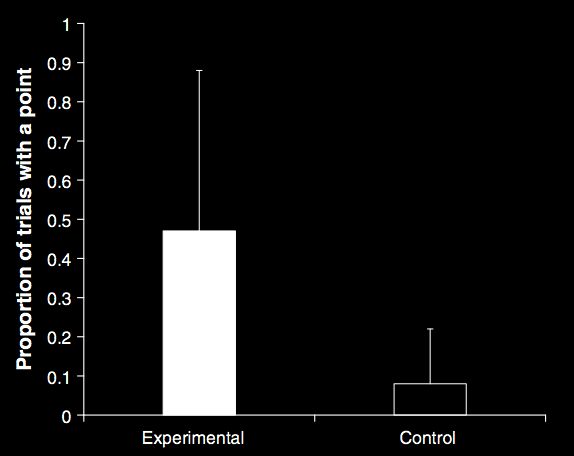

Liszkowski et al 2008, figure 3

Liszkowski et al 2008, figure 3

Liszkowski et al 2008, figure 5

From around 11 or 12 months of age, humans spontaneously use pointing to ...

- request

- inform

- initiate joint engagement (‘Wow! That!’)

How do infants understand pointing actions?

Hypothesis 1: Pure use (compare block & slab).

pointing: referent and context

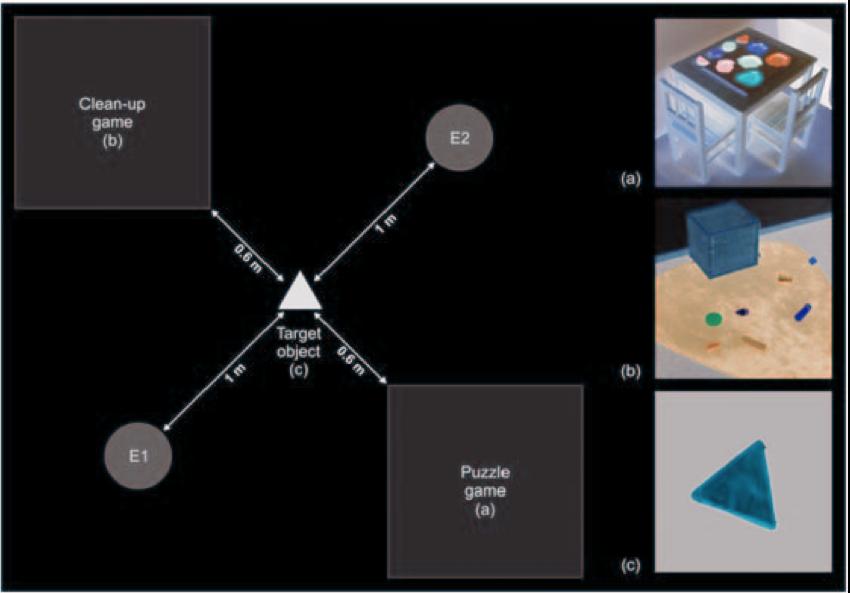

Liebal et al 2009, figure 1

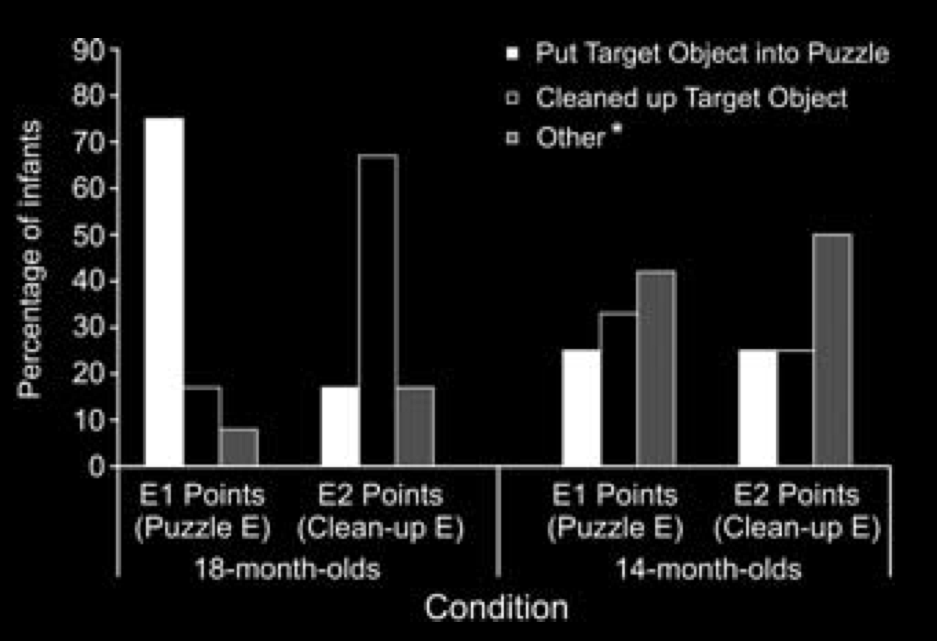

Liebal et al 2009, figure 2

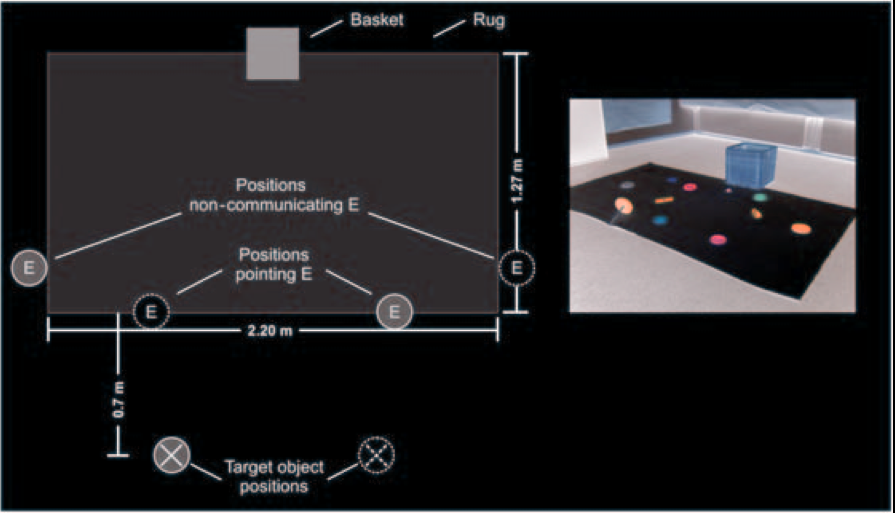

Liebal et al 2009, figure 3

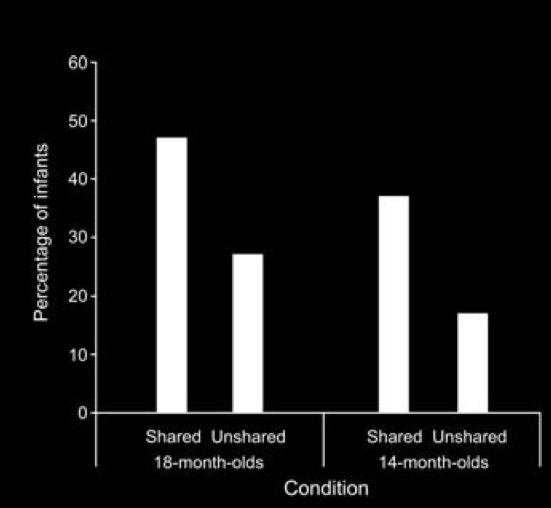

Liebal et al 2009, figure 4

How do infants understand pointing actions?

Hypothesis 1: Pure use (compare block & slab).

A Puzzle about Pointing

How do infants understand pointing actions?

Hypothesis 2: ‘shared intentionality’

shared intentionality

‘infant pointing is best understood---on many levels and in many ways---as depending on uniquely human skills and motivations for cooperation and shared intentionality, which enable such things as joint intentions and joint attention in truly collaborative interactions with others (Bratman, 1992; Searle, 1995).’

Tomasello et al (2007, p. 706)

Why suppose this?

Hare & Tomasello, 2004

‘to understand pointing, the subject needs to understand more than the individual goal-directed behaviour. She needs to understand that by pointing towards a location, the other attempts to communicate to her where a desired object is located’

Moll & Tomasello, 2007 p. 6

What is a communicative action?

(What does someone understand when she understands that another communicates with her?)

Ayesha waves at Ben to get him to come over.

Goal: get Ben to come over

Means: get Ben to recognise that I intend to get Ben to come over

Intention: to get Ben to come over by means of getting Ben to recognise that I intend to get Ben to come over.

What is a communicative action?

First approximation: An action done with an intention to provide someone with evidence of an intention with the further intention of thereby fulfilling that intention

(compare Grice 1989: chapter 14)

Hare & Tomasello, 2004

‘to understand pointing, the subject needs to understand more than the individual goal-directed behaviour. She needs to understand that by pointing towards a location, the other attempts to communicate to her where a desired object is located’

Moll & Tomasello, 2007 p. 6

First approximation: An action done with an intention to provide someone with evidence of an intention with the further intention of thereby fulfilling that intention

(compare Grice 1989: chapter 14)

The confederate means something in pointing at the left box if she intends:

- \item that you open the left box;

- \item that you recognize that she intends (1), that you open the left box; and

- \item that your recognition that she intends (1) will be among your reasons for opening the left box.

(Compare Grice, 1967 p. 151; Neale, 1992 p. 544)

Inconsistent tetrad

1. 11- or 12-month-old infants produce and understand declarative pointing gestures.

2. Producing or understanding pointing gestures involves understanding communicative actions.

3. A communicative action is an action done with an intention to provide someone with evidence of an intention with the further intention of thereby fulfilling that intention.

4. Pointing facilitates the developmental emergence of sophisticated cognitive abilities including mindreading.

From Joint Action to Communication

grasping / orienting vs referring

individual vs joint

From pointing to one-word utterances ...

Tincoff and Jusczyk 2011, figure 1

Tincoff and Jusczyk 2011, figure 1

grasping / orienting vs referring

individual vs joint

understanding action

R(a,G) defined with intention

R(a,G) defined non-psychologically

joint action

R(a1, a2, ..., G) defined with shared intention

R(a1, a2, ..., G) defined with expectations about collective goals

communication

Refers(gesture,object) defined with communicative intention

R(gesture,object) defined non-psychologically

Inconsistent tetrad

1. 11- or 12-month-old infants produce and understand declarative pointing gestures.

2. Producing or understanding pointing gestures involves understanding communicative actions.

3. A communicative action is an action done with an intention to provide someone with evidence of an intention with the further intention of thereby fulfilling that intention.

4. Pointing facilitates the developmental emergence of sophisticated cognitive abilities including mindreading.

Syntax / Innateness

core knowledge of

- physical objects

- [colour]

- mental states

- action

- number

- ...

- The turnip of shapely knowing isn't yet buttressed by death.

- *The buttressed turnip shapely knowing yet isn't of by death.

core knowledge of syntax is innate (?)

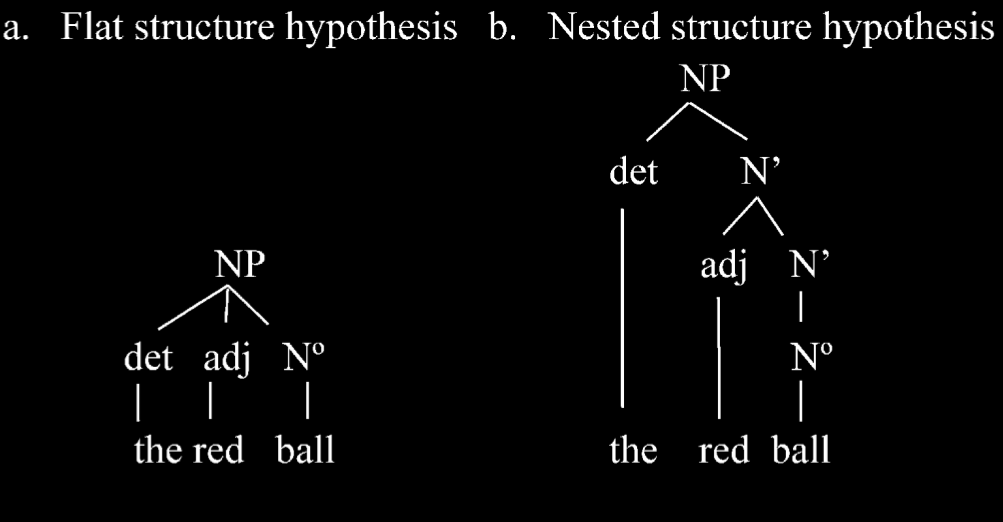

the red ball

‘I’ll play with this red ball and you can play with that one.’

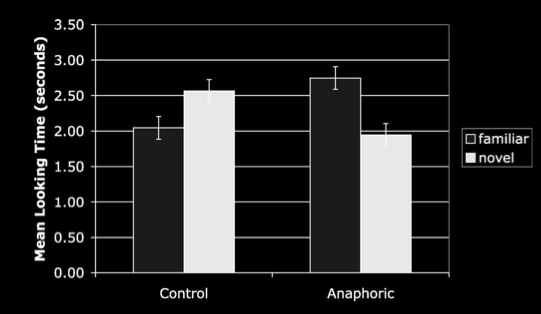

Lidz et al (2003)

- \item ‘red ball’ is a constituent on (b) but not on (a)

- \item anaphoric pronouns can only refer to constituents

- \item In the sentence ‘I’ll play with this red ball and you can play with that one.’, the word ‘one’ is an anaphoric prononun that refers to ‘red ball’ (not just ball). \citep{lidz:2003_what,lidz:2004_reaffirming}.

infants?

| Look, a yellow bottle! | control: What do you see now? test: Do you see another one? |

|

| [yellow bottle] | [yellow bottle] | [blue bottle] |

Lidz et al (2003)

Lidz et al (2003, figure 1)

From 18 months of age or earlier, infants represent the syntax of noun phrases in much the way adults do.

But are these representations innate?

Poverty of stimulus argument

-

\itemHuman infants acquire X.

-

\itemTo acquire X by data-driven learning you'd need this Crucial Evidence.

-

\itemBut infants lack this Crucial Evidence for X.

-

\itemSo human infants do not acquire X by data-driven learning.

-

\itemBut all acquisition is either data-driven or innately-primed learning.

-

\itemSo human infants acquire X by innately-primed learning .

compare Pullum & Scholz 2002, p. 18

‘the APS [argument from the poverty of stimulus] still awaits even a single good supporting example’

Pullum & Scholz 2002, p. 47

What is innate in humans?

- What evidence is there?

- What does the evidence show is innate?

- Type: knowledge, core knowledge, modules, concepts, abilities, dispositions ...

- Content: e.g. universal grammar, principles of object perception, minimal theory of mind ...

Innateness / Syntax Conclusions

- Adults have inaccessible, domain-specific representations concerning the syntax of natural languages.

- So do infants (from 18 months of age or earlier, well before they can use the syntax in production).

- These representations are a paradigm case of core knowledge.

- These representations plausibly enable understanding and play a key role in the development of abilities to communicate with language.

development as rediscovery

Conclusions and Questions

the question

no big idea

(case-by-case approach)

‘if you want to describe what is going on in the head of the child when it has a few words which it utters in appropriate situations, you will fail for lack of the right sort of words of your own.

‘We have many vocabularies for describing nature when we regard it as mindless, and we have a mentalistic vocabulary for describing thought and intentional action; what we lack is a way of describing what is in between’

(Davidson 1999, p. 11)

core knowledge of

- actions

- syntax (?)

- minds

- causal interactions

- physical objects

- colours (?)

- (number)

- (space)

What is core knowledge?

Is it all one thing?

Does it exist in adults?

How does it relate to knowledge knowledge?

(How does it relate to nonhumans' cognition?)

- Core knowledge exists.

- There is a gap between core knowledge and knowledge knowledge.

- Crossing the gap involves social interactions, perhaps involving words.

Minimal approaches

to joint action

and referential communication

do not presuppose

and may therefore explain

knowledge knowledge.

development as rediscovery