Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Unperceived Objects: An Illustration of Davidon's Challenge

plan

objects

causes

colours

words

non-verbal communications

minds

actions

When do humans first come to know facts about the locations of objects they are not perceiving?

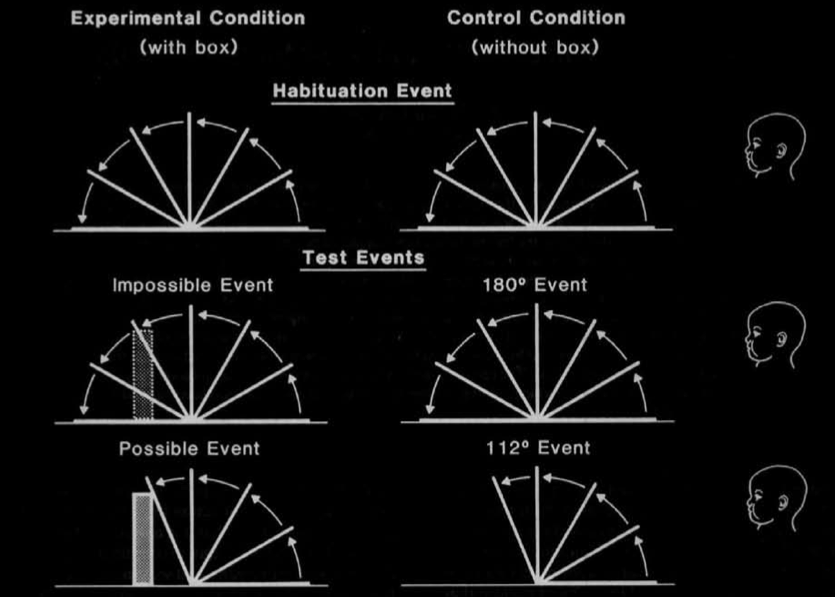

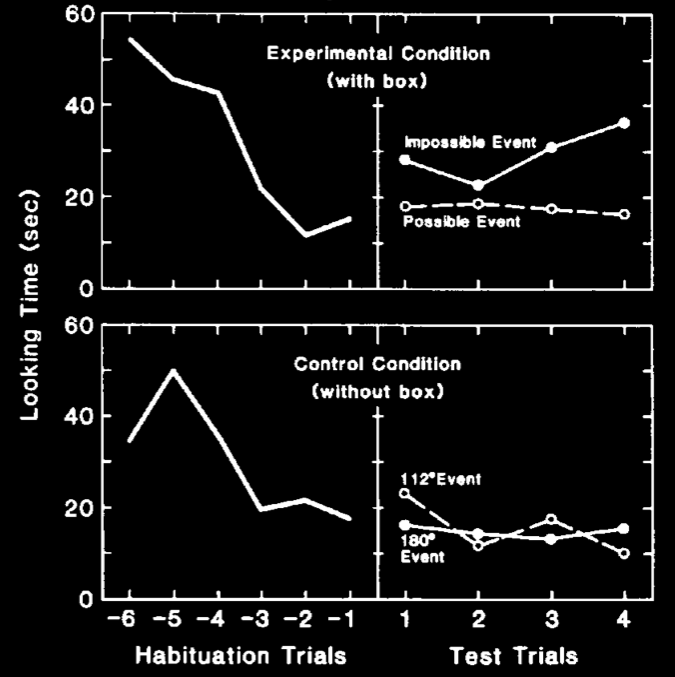

Baillargeon (1987, figure 1)

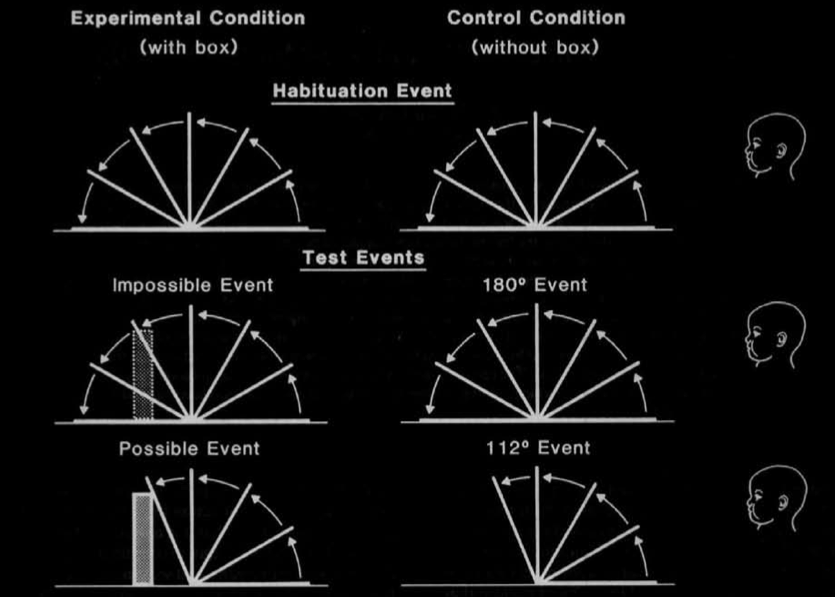

source: Baillargeon et al (1987, figure 2)

When do humans first come to know facts about the locations of objects they are not perceiving?

look: by 4 months of age or earlier (Baillargeon 1987).

look: by around 2.5 months of age or earlier (Aguiar & Baillargeon 1999)

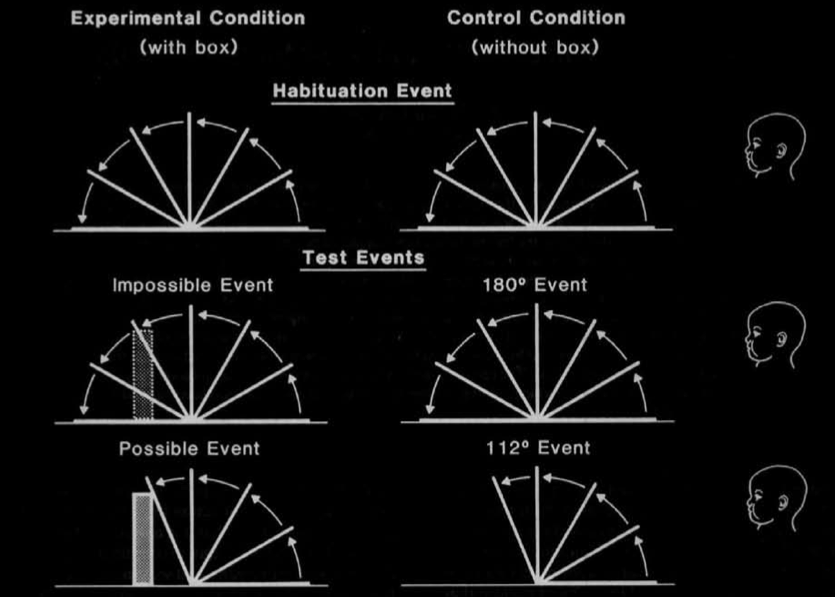

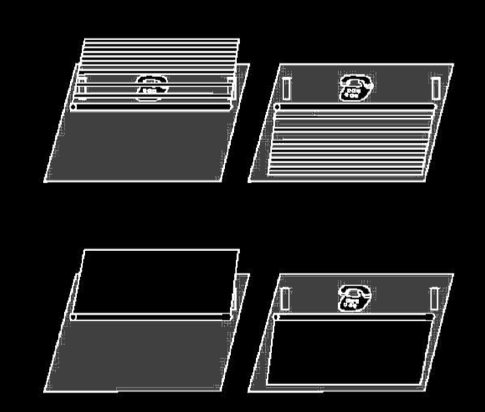

Shinskey and Munakata 2001, figure 1

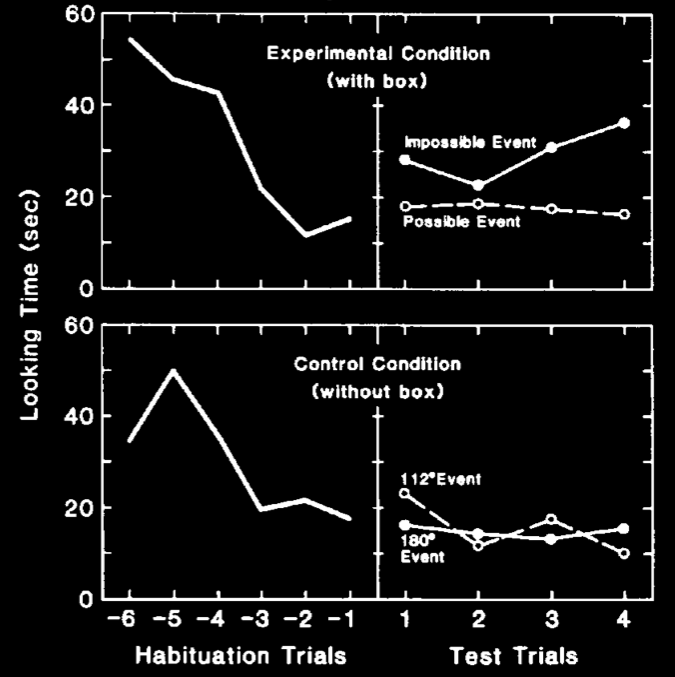

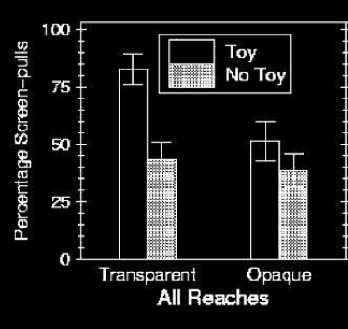

Shinskey and Munakata 2001, figure 2

When do humans first come to know facts about the locations of objects they are not perceiving?

look: by 4 months of age or earlier (Baillargeon 1987).

look: by around 2.5 months of age or earlier(Aguiar & Baillargeon 1999)

search: not until after 7 months of age (Shinskey & Munakata 2001)

‘action demands are not the only cause of failures on occlusion tasks’

Shinskey (2012, p. 291)

‘the tip of an iceberg’ Charles & Rivera (2009, p. 994)

What is the problem?

Uncomplicated Account of Minds and Actions

For any given proposition [There’s a spider behind the book] and any given human [Wy] ...

1. Either Wy knows that there’s a spider behind the book, or she does not.

2. Either Wy can act for the reason that there is, or seems to be, a spider behind the book (where this is her reason for acting), or else she cannot.

3. The first alternatives of (1) and (2) are either both true or both false.

‘if you want to describe what is going on in the head of the child when it has a few words which it utters in appropriate situations, you will fail for lack of the right sort of words of your own.

‘We have many vocabularies for describing nature when we regard it as mindless, and we have a mentalistic vocabulary for describing thought and intentional action; what we lack is a way of describing what is in between’

(Davidson 1999, p. 11)

‘there are many separable systems of mental representations ... the task ... is to ... [find] the distinct systems of mental representation and to understand their development and integration’\citep[p.\ 1522]{Hood:2000bf}.

(Hood et al 2000, p. 1522)

summary