Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Two Breakthroughs

Recall that the question for this course is ...

Our focus is on two breakthrough sets of findings.

One concerns core knowledge, the other social interaction.

core knowledge

Take core knowledge first.

We will see that infants can tackle physics, number, agents and minds thanks to a set of

innate or early-developing abilities, often labelled `core knowledge'.

We don't understand it.

For now, let us use the term `core knowledge' to mean whatever infants have concerning

the locations of particular objects which is not knowledge but which underpins their

abilities to discriminate between phyiscally possible and physically impossible

sitatuions where the difference between possibile and impossibile depends on facts about

objects the infants are not currently perceiving.

It is important that we don't (yet) know what core knowledge is; `core knowledge' is a

term of art. I haven't explained what it is.

[*needs updating!]

Our position is this.

Some scientists talk about core knowledge, and formulate hypotheses in terms of it.

Since these hypotheses are supported by evidence, we can reasonably suppose they are true.

So there are some things we provisionally suppose are truths about core knowledge.

For instance, infants' core knowledge enables them to represent unperceived objects.

So we know some truths about core knowledge, but we don't know what it is.

You'd probably prefer it if I could tell you what core knowledge is first.

But here we have to work backwards.

We have to gather truths about this unknown thing, core knowledge.

And then we have to ask, What could core knowledge be given that these things are true?

Is like knowledge:

- guides behaviour

- involves something like inference

- concerns abstract features

Is unlike knowledge:

- no inferential integration

- judgement-independent

- domain-specific

- signature limits

Several features distinguish core knowledge from adult-like understanding: its content is

unknowable by introspection and judgement-independent; it is specific to quite narrow

categories of event and does not grow by means of generalization; it is best understood

as a collection of rules rather than a coherent theory; and it has limited application

being usually manifest in the control of attention (as measured by dishabituation, gaze,

and looking times) and rarely or never manifest in purposive actions such as reaching.

social interaction

Now, what about social interaction? First let me mention what people say about it.

Preverbal infants manfiest a surprising range of social abilities.

These include imitation, which can occur just days and even minutes after birth

(Meltzoff & Moore 1977; Field et al. 1982; Meltzoff & Moore 1983), imitative learning

(Carpenter et al. 1998), gaze following (Csibra & Volein 2008), goal ascription

(Gergely et al. 1995; Woodward & Sommerville 2000), social referencing (Baldwin 2000)

and pointing (Liszkowski et al. 2006).

Taken together, the evidence reveals that preverbal infants have surprisingly rich

social abilities.

- imitation

- gaze following

- secondary intersubjectivity

- social referencing

- pointing

- goal ascription

- joint action

- language creation

Perhaps the best evidence how sophisticated infant social interaction can be comes

from studies of language creation.

(This will be a key topic when we come to study knowledge of language, but let me

give you a tiny preview.)

Children with no experience of others' languages can create their own languages.

We know this from studies of profoundly deaf children brought up in purely oral

environments and therefore without experience of language

\citep{Kegl:1999es,Senghas:2001zm,Goldin-Meadow:2003pj}.

Individually or in groups these children invent their own signed languages.

These languages are not as rich as those of children with experience of other

people's languages but they have all of the essential features of language

including lexicons and syntax (*refs: Goldin-Meadow 2002, 2003).

The children invent gesture forms for words which they use with the same meanings

in different contexts, they adopt standard orderings for combining words into

sentences, and they use sentences in constructing narratives about past, present,

future and hypothetical events (*ref: Goldin-Meadow 2003: 170).

But it is not just children in extreme circumstances that create words.

Children in ordinary environments will create their own words before they learn to

use those of the adults; when children start speaking, it is often the adults who

are learning new words.

(‘Some children are so impatient that they coin their own demonstrative pronoun. For

instance, at the age of about 12 months, Max would point to different objects and

say “doh?,” sometimes with the intent that we do something with the objects, such as

bring them to him, and sometimes just wanting us to appreciate their existence’

(\citealp[p.\ 122]{Bloom:2000qz}; see further \citealp{Clark:1981bi,Clark:1982hj}).)

And even where children have mastered a lexical convention, they will readily violate

it in their own utterances in order to get a point across.

(‘From the time they first use words until they are about two or two-and-a-half,

children noticeably and systematically overextend words. For example, one child used

the word “apple” to refer to balls of soap, a rubber-ball, a ball-lamp, a tomato,

cherries, peaches, strawberries, an orange, a pear, an onion, and round biscuits’

\citep[p.\ 35]{Clark:1993bv}.)

core knowlegde + social interaction

One problem for us is that these two sets of findings are typically considered in

isolation,

although I think there are strong reasons to suppose that understanding the origins

of knowledge

will require thinking about both core knowledge and social interaction.

One of our challenges will be to understand how core knowledge and social interaction

conspire in driving the emergence of knowledge in particular domains.

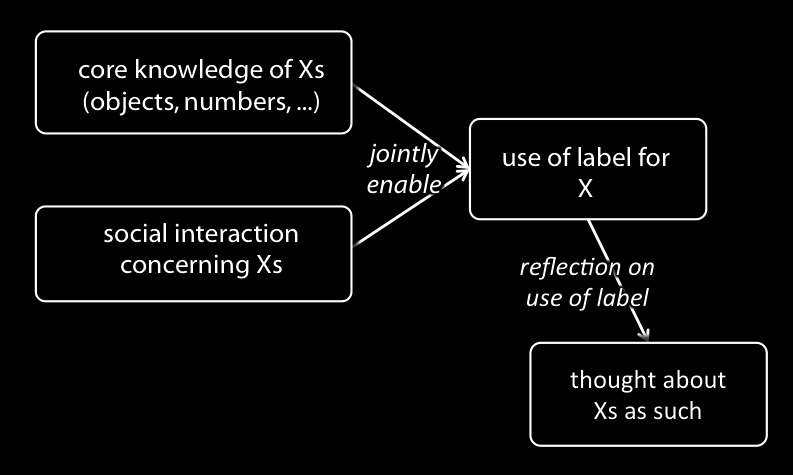

working hypothesis:

core knowledge in certain domains is necesary

for early forms of social interaction

and these forms of social interaction are necessary

to get from core knowledge of Xs to knowledge proper of Xs

My working hypothesis (in two parts)

is that core knowledge in certain domains is necesary for early forms of

social interaction

and that these early forms of social interaction are necessary to get from core knowledge

to knowledge knowledge.

development as rediscovery

The idea, in essence, is that cognitive development is a kind of rediscovery.

(But not exactly as Plato's myth had it.)

How do humans get from core knowledge to knowledge knowledge?

I want to suggest that it involves a process of rediscovery.

I don't think it's a case of partial knowledge becoming gradually more complete, or of

the core knowledge providing content for later knowledge states.

Rather, I think the core knowledge shapes the

subject's body, behaviour and attention in ways that facilitate discovery at the next stage.

And, most importantly, core knowledge enables increasingly sophisticated forms of social

interaction.

It is these social interactions---together with the bodily, behavioural and mental changes---that

enable subsequent re-discoveries.

So, on this view, the role of some early-developing abilities in explaining the later acquisition

of conceptual understanding does not involve direct representational connections;

rather the early developing abilities facilitate or enable social interaction,

influence attention and inform behaviour;

and these influences facilitate development.

To make this vague idea slightly more concrete, let me zoom in.

I think having verbal labels for things sometimes helps with acquiring concepts of them.

Now this sounds paradoxical.

Doesn't having a label for something mean being able to label correctly?

And how could you label correctly without the corresponding concept?

My suggestion is that having core knowledge is not having a concept (many disagree);

but core knowledge could underpin your correct use of a label.

Now labels are acquired through social interaction, or so I suggested earlier.

Hence the picture.

Now this picture needs two qualifications.

First, it's missing some details, and these details will vary from case to case

(what's true of knowledge of objects might not be true of knowledge of number).

Second, the picture might be completely wrong.

But even if the picture is wrong, I'll bet that social interaction and core knowledge are both

essential for explaining how humans come to know things.

So I don't claim to know how these two are necessary, only that they are.

In fact my aim isn't primarily to explain to you how these two factors explain the origins of

mind.

Instead my hope is this.

I'll give you the background on social interaction and core knowledge.

And you'll tell me how these two (or perhaps other factors) are involved in explaining how

humans come to know things about objects, colours, actions, numbers and the rest.