Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Syntax / Innateness

core knowledge of

- physical objects

- [colour]

- mental states

- action

- number

- ...

- The turnip of shapely knowing isn't yet buttressed by death.

- *The buttressed turnip shapely knowing yet isn't of by death.

core knowledge of syntax is innate (?)

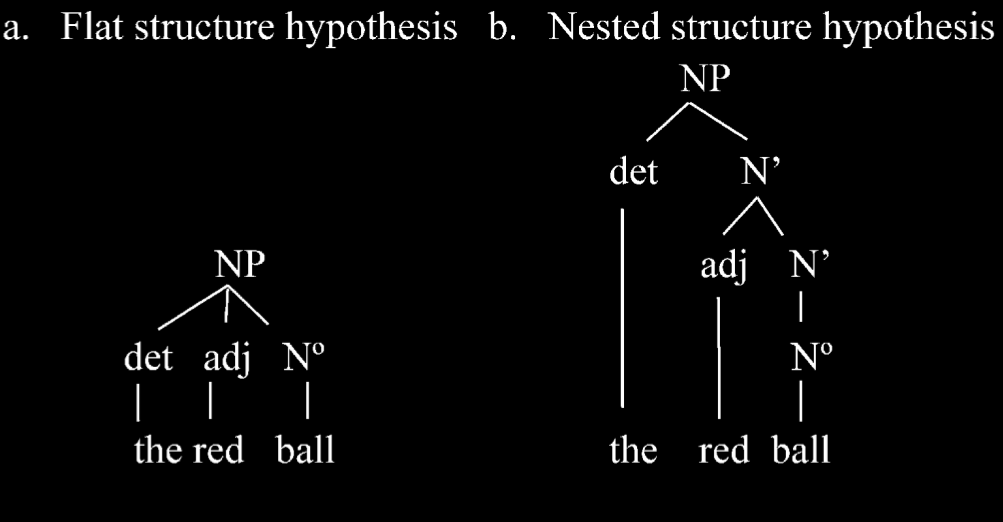

the red ball

‘I’ll play with this red ball and you can play with that one.’

Lidz et al (2003)

- \item ‘red ball’ is a constituent on (b) but not on (a)

- \item anaphoric pronouns can only refer to constituents

- \item In the sentence ‘I’ll play with this red ball and you can play with that one.’, the word ‘one’ is an anaphoric prononun that refers to ‘red ball’ (not just ball). \citep{lidz:2003_what,lidz:2004_reaffirming}.

infants?

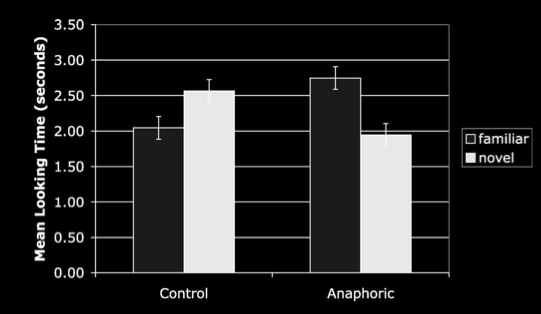

| Look, a yellow bottle! | control: What do you see now? test: Do you see another one? |

|

| [yellow bottle] | [yellow bottle] | [blue bottle] |

Lidz et al (2003)

Lidz et al (2003, figure 1)

From 18 months of age or earlier, infants represent the syntax of noun phrases in much the way adults do.

But are these representations innate?

Poverty of stimulus argument

-

\itemHuman infants acquire X.

-

\itemTo acquire X by data-driven learning you'd need this Crucial Evidence.

-

\itemBut infants lack this Crucial Evidence for X.

-

\itemSo human infants do not acquire X by data-driven learning.

-

\itemBut all acquisition is either data-driven or innately-primed learning.

-

\itemSo human infants acquire X by innately-primed learning .

compare Pullum & Scholz 2002, p. 18

‘the APS [argument from the poverty of stimulus] still awaits even a single good supporting example’

Pullum & Scholz 2002, p. 47

What is innate in humans?

- What evidence is there?

- What does the evidence show is innate?

- Type: knowledge, core knowledge, modules, concepts, abilities, dispositions ...

- Content: e.g. universal grammar, principles of object perception, minimal theory of mind ...

Innateness / Syntax Conclusions

- Adults have inaccessible, domain-specific representations concerning the syntax of natural languages.

- So do infants (from 18 months of age or earlier, well before they can use the syntax in production).

- These representations are a paradigm case of core knowledge.

- These representations plausibly enable understanding and play a key role in the development of abilities to communicate with language.

development as rediscovery