Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Core Knowledge vs Object Indexes

The CLSTX conjecture:

Five-month-olds’ abilities to track briefly unperceived objects

are not grounded on belief or knowledge:

instead

they are consequences of the operations of

a system of object indexes.

Leslie et al (1989); Scholl and Leslie (1999); Carey and Xu (2001)

‘if you want to describe what is going on in the head of the child when it has a few words which it utters in appropriate situations, you will fail for lack of the right sort of words of your own.

‘We have many vocabularies for describing nature when we regard it as mindless, and we have a mentalistic vocabulary for describing thought and intentional action; what we lack is a way of describing what is in between’

(Davidson 1999, p. 11)

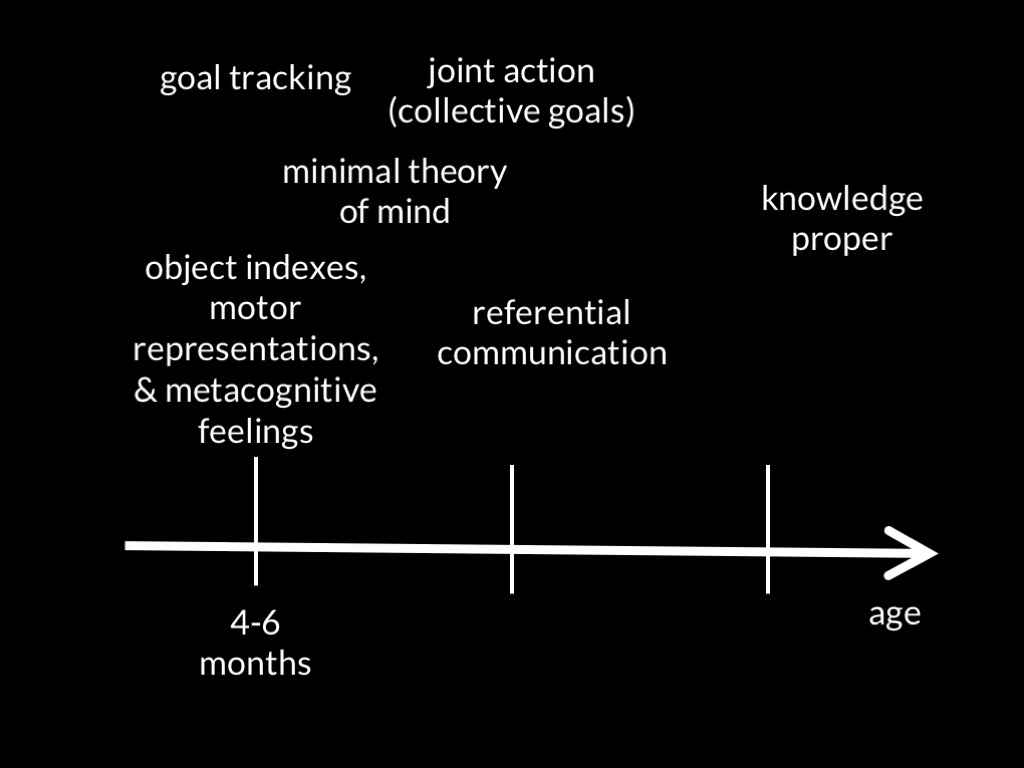

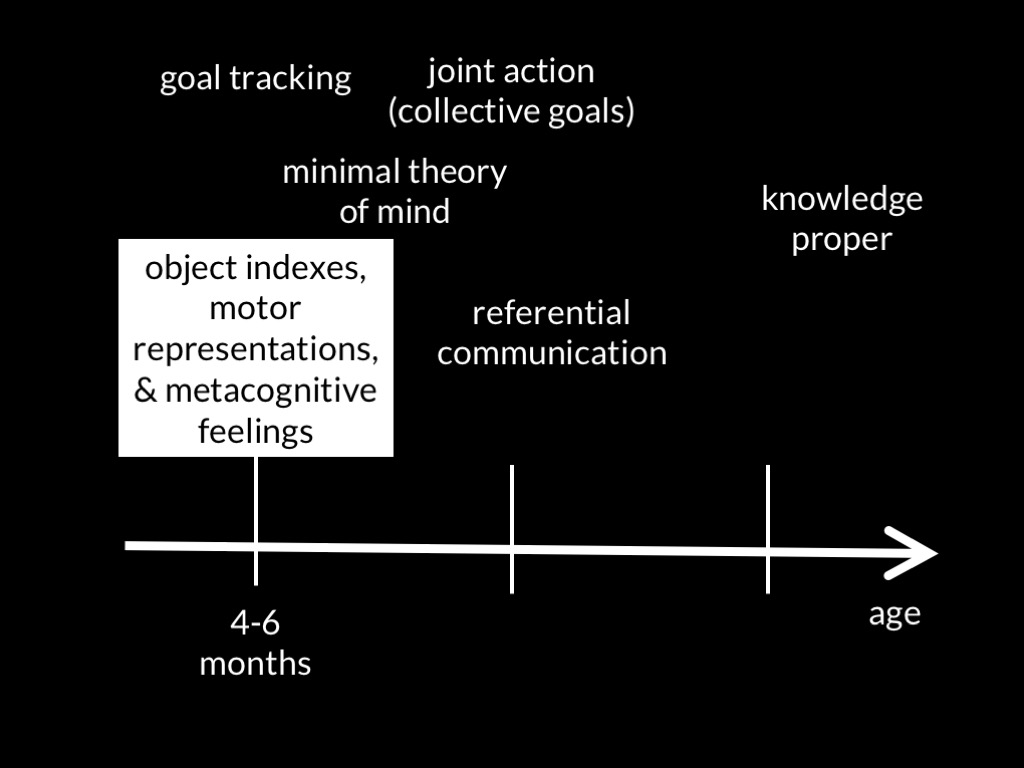

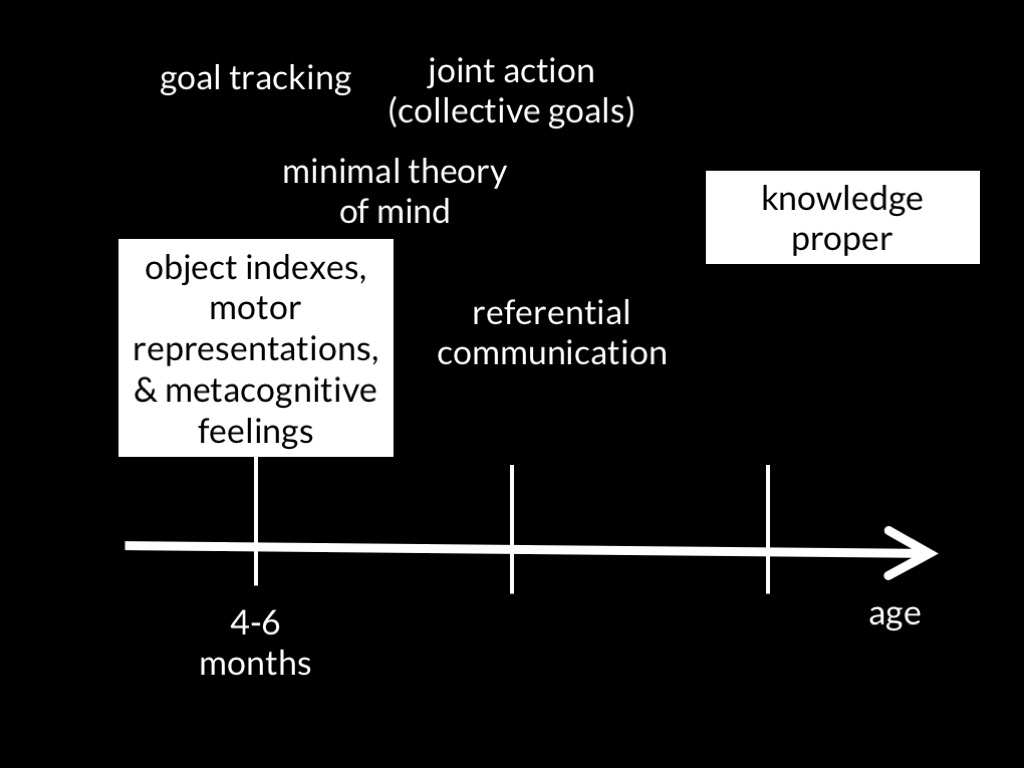

infant

adult

social interaction

language

time --->

The Core Knowledge View?

‘Just as humans are endowed with multiple, specialized perceptual systems, so we are endowed with multiple systems for representing and reasoning about entities of different kinds.’

Carey and Spelke, 1996 p. 517

‘core systems are

- largely innate

- encapsulated

- unchanging

- arising from phylogenetically old systems

- built upon the output of innate perceptual analyzers’

(Carey and Spelke 1996: 520)

representational format: iconic (Carey 2009)

The Core Knowledge View

Infants, like most adults, do not know the principles of object perception; but they have core knowledege of them.

The CLSTX conjecture

The principles of object perception characterise how a system of object indexes should work.

Infants’ (and adults’) object indexes track objects through occlusion.

Five-month-olds do not know the location of an occluded object.

Five-month-olds can have metacognitive feelings caused by discrepancies in its location.

Next Problem

Assigning Object Indexes Isn’t Having Knowledge

... so how can we explain the developmental origins of knowledge?