Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

The Motor Theory of Goal Tracking

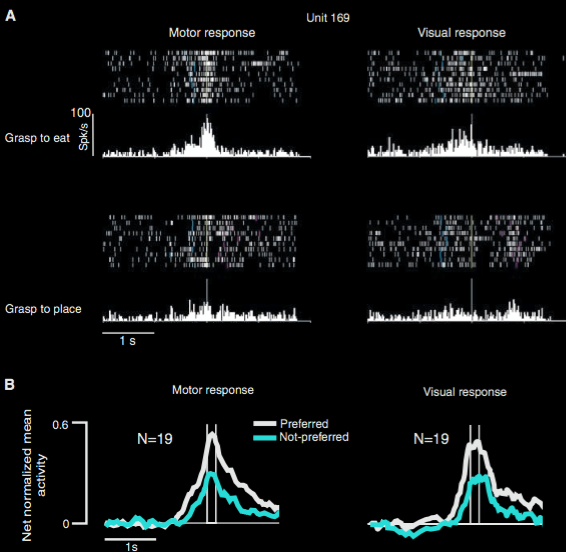

Fogassi et al 2005, figure 5

The Double Life of Motor Representation

What are those motor representations doing here?

Motor Theory of Goal Tracking (including Speech Perception)

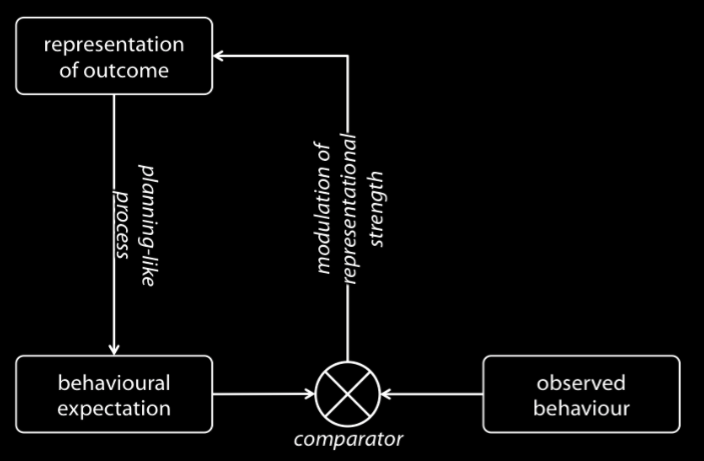

Sinigalia & Butterfill 2015, figure 1

Pure goal-tracking could,

in principle,

be implemented motorically.

Motor Conjecture

In 9-month-olds,

all pure goal-tracking is explained by the Motor Theory;

---

‘we believe that the three proposed mechanisms of goal attribution [...] complement each other’

Csibra & Gergely, 2007 p. 74

How?

Infants can track goals from nine months of age (or earlier).

Why?

In infants (and adults),

goal-tracking is limited by their abilities to act.

The ‘Teleological Stance’

~ The goals of an action are those outcomes which the means is a best available way of bringing about.

Csibra & Gergely

Tracking

1. This means, m, has been adopted (observation)

2. G is an outcome such that: m is a best available* way of bringing G about

3. ∴ G is a goal of the observed action

‘simulation is clearly a natural and effective way to find the most efficient action towards a goal state.’

Csibra & Gergely, 2007 p. 72

| The Simple View | Motor Conjecture | |

| What is the function to be computed? | [Teleological Stance] | [Teleological Stance] |

| How is this function computed? | By reasoning from beliefs. | By using motor processes ‘in reverse’. |

| Why is goal-tracking limited by action ability? | ??? | Because both rely on motor processes. |