Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

A Puzzle About Goal Tracking

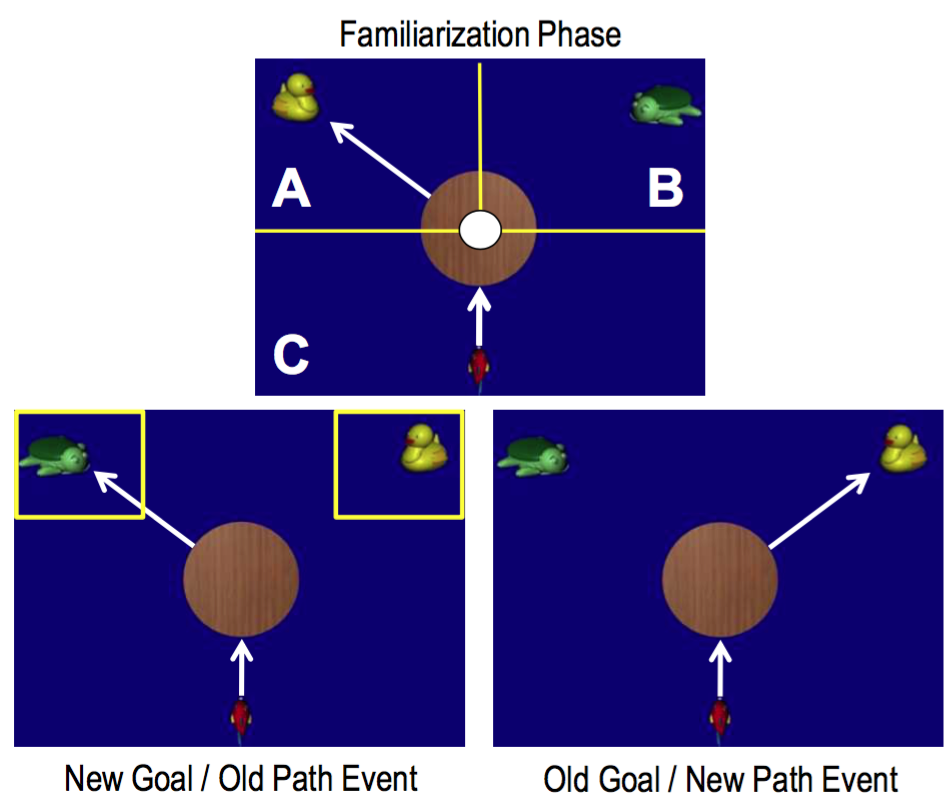

Kanakogi and Itakura, 2011 figure 1C (part)

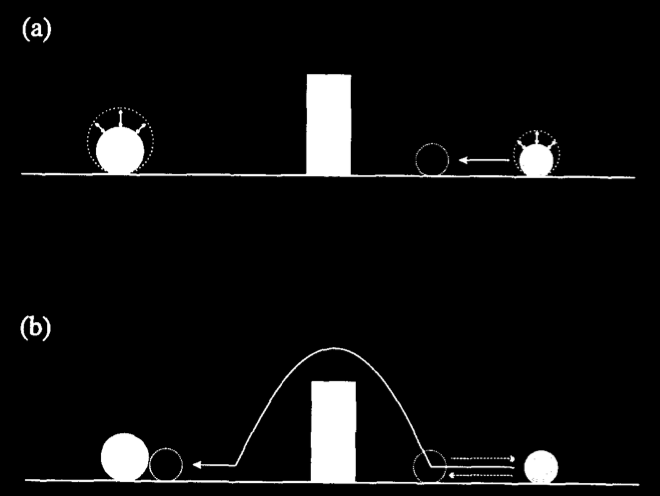

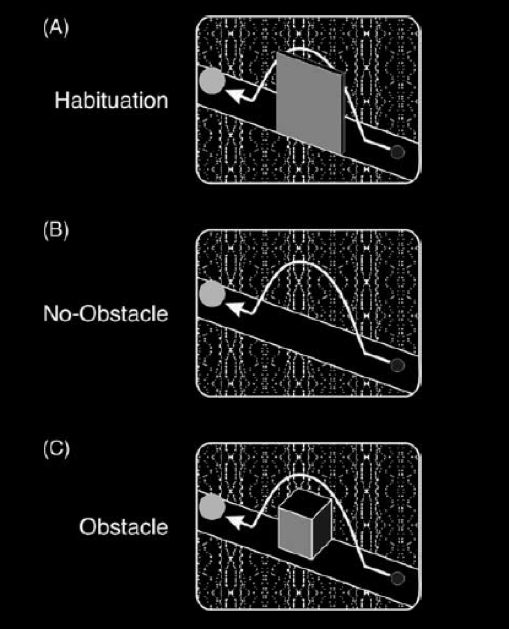

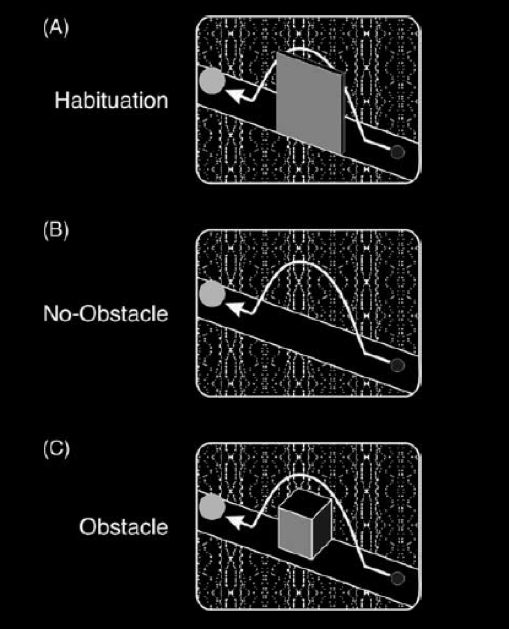

Gergely et al 1995, figure 1

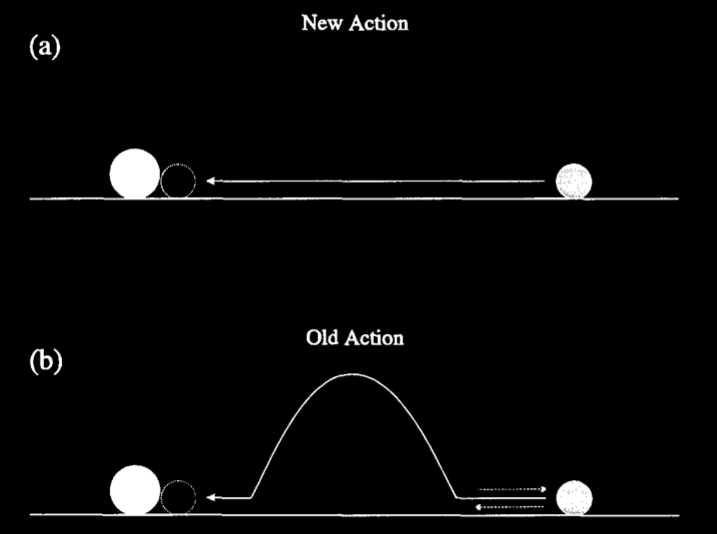

Gergely et al 1995, figure 3

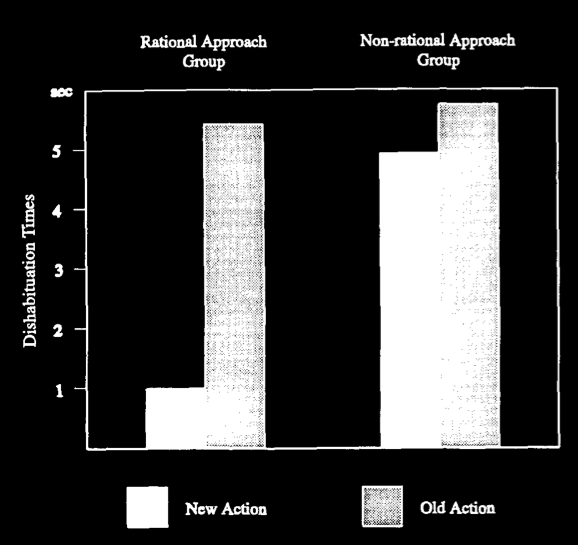

Gergely et al 1995, figure 5

Heider and Simmel, figure 1

Csibra et al 2003, figure 6

Puzzle

In infants under 10 months,

it appears that

some,

but not all,

goal-tracking is limited by their abilities to act.

Daum et al, 2012 figure 1

Daum et al, 2012 figure 2

Puzzles

In infants under 10 months,

it appears that

some,

but not all,

goal-tracking is limited by their abilities to act ...

... and that goal-tracking sometimes manifests in dishabitution or pupil dilation but not proactive gaze.