Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Perceptual Animacy

Perceptual Animacy

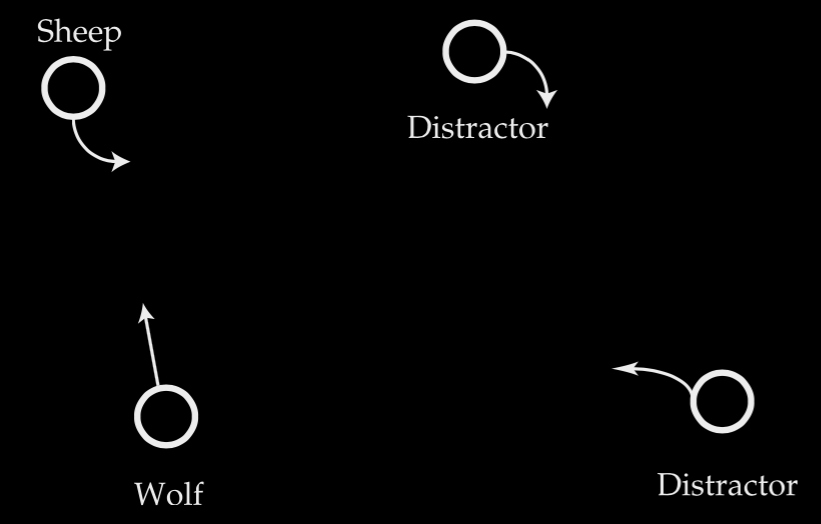

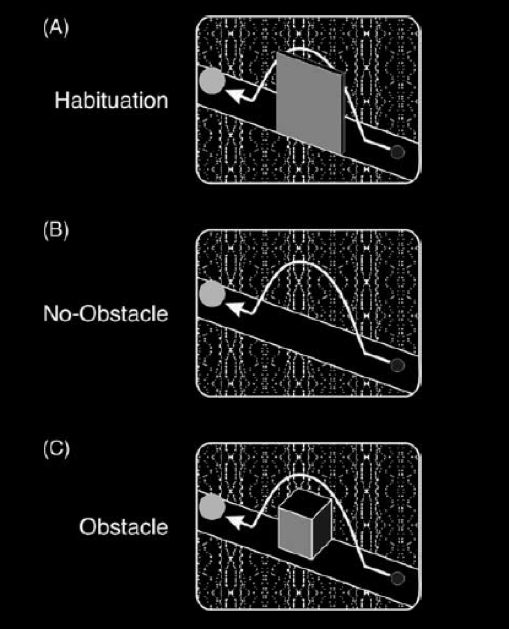

Gao et al, 2009 figure 2

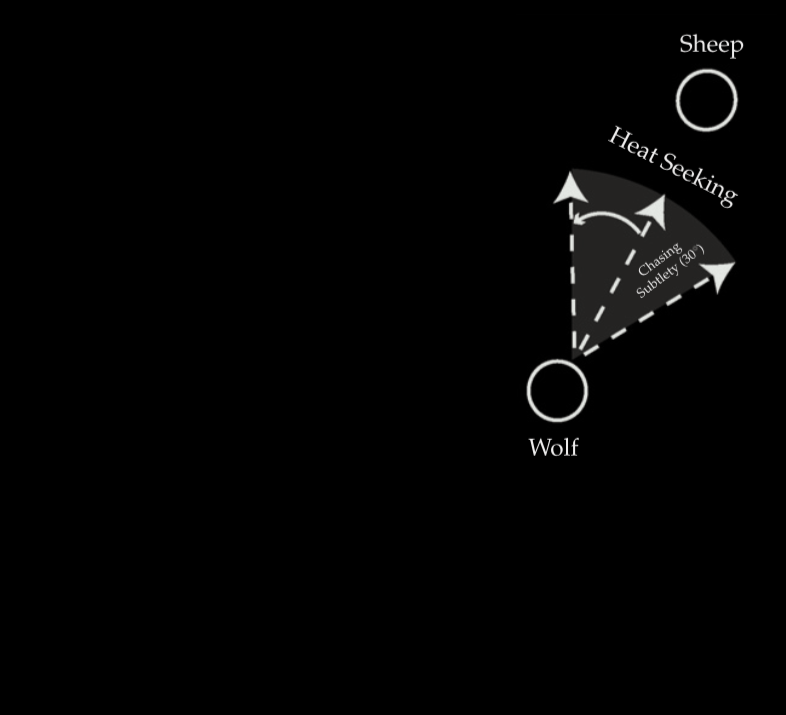

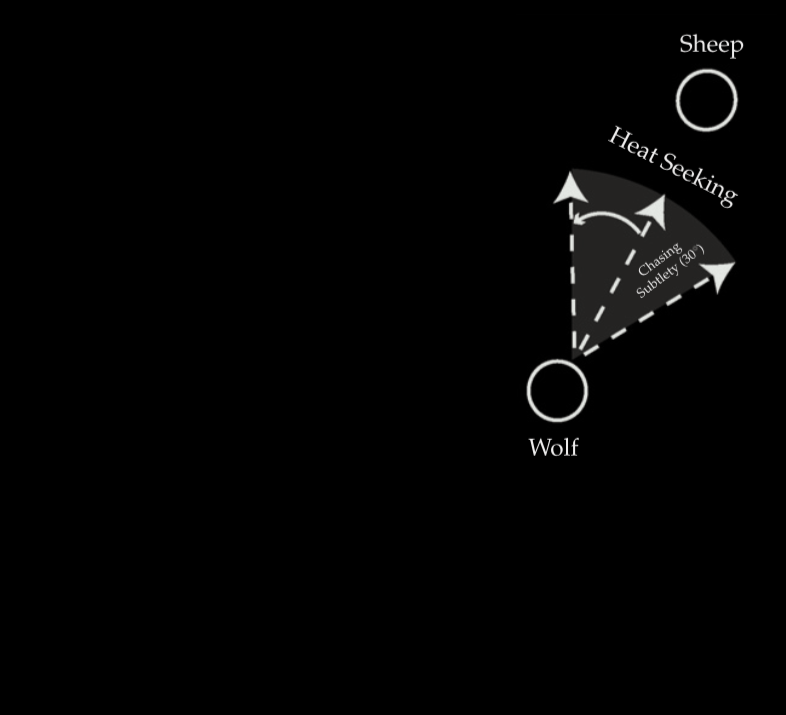

Gao et al, 2009 figure 3b

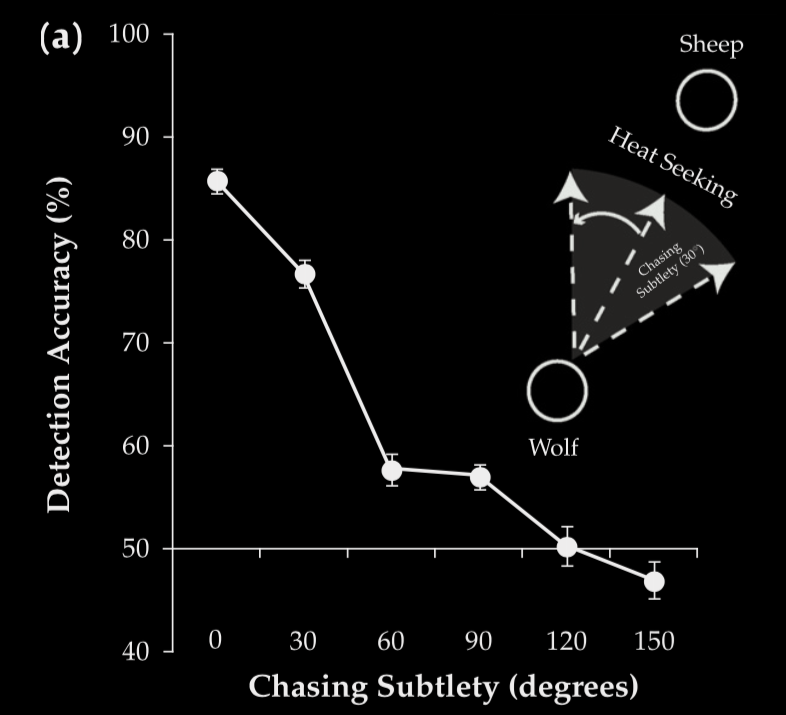

Gao et al, 2009 figures 3b, 4a

| pure goal-tracking | perceptual animacy | |

| What is tracked? | actions & goals | animate objects & targets |

| Computational description? | Teleological Stance | spatio-temporal heuristics (e.g. subtlety, directionality) |

| Processes & representations? | motoric | perceptual |

Motor Conjecture Revised

In 9-month-olds,

all pure goal-tracking is explained by the Motor Theory;

appearances that goal-tracking is not limited by their abilities to act are due to perceptual animacy.

Predictions

Where 9-month-olds appear to be tracking goals

in ways not limited by their abilities to act,

they will be subject to signature limits of perceptual animacy

(e.g. subtlety, directionality);

and the processes underlying their abilities will be broadly perceptual.

Puzzles

In infants under 10 months,

it appears that

some,

but not all,

goal-tracking is limited by their abilities to act ...

... and that goal-tracking sometimes manifests in dishabitution or pupil dilation but not proactive gaze.

objection

Gao et al, 2009 figure 3b; Csibra et al 2003, figure 6

further complication: associative learning for sequencing

Gredebäck & Melinder, 2010