Let me first explain something about this notion of a collective goal ...

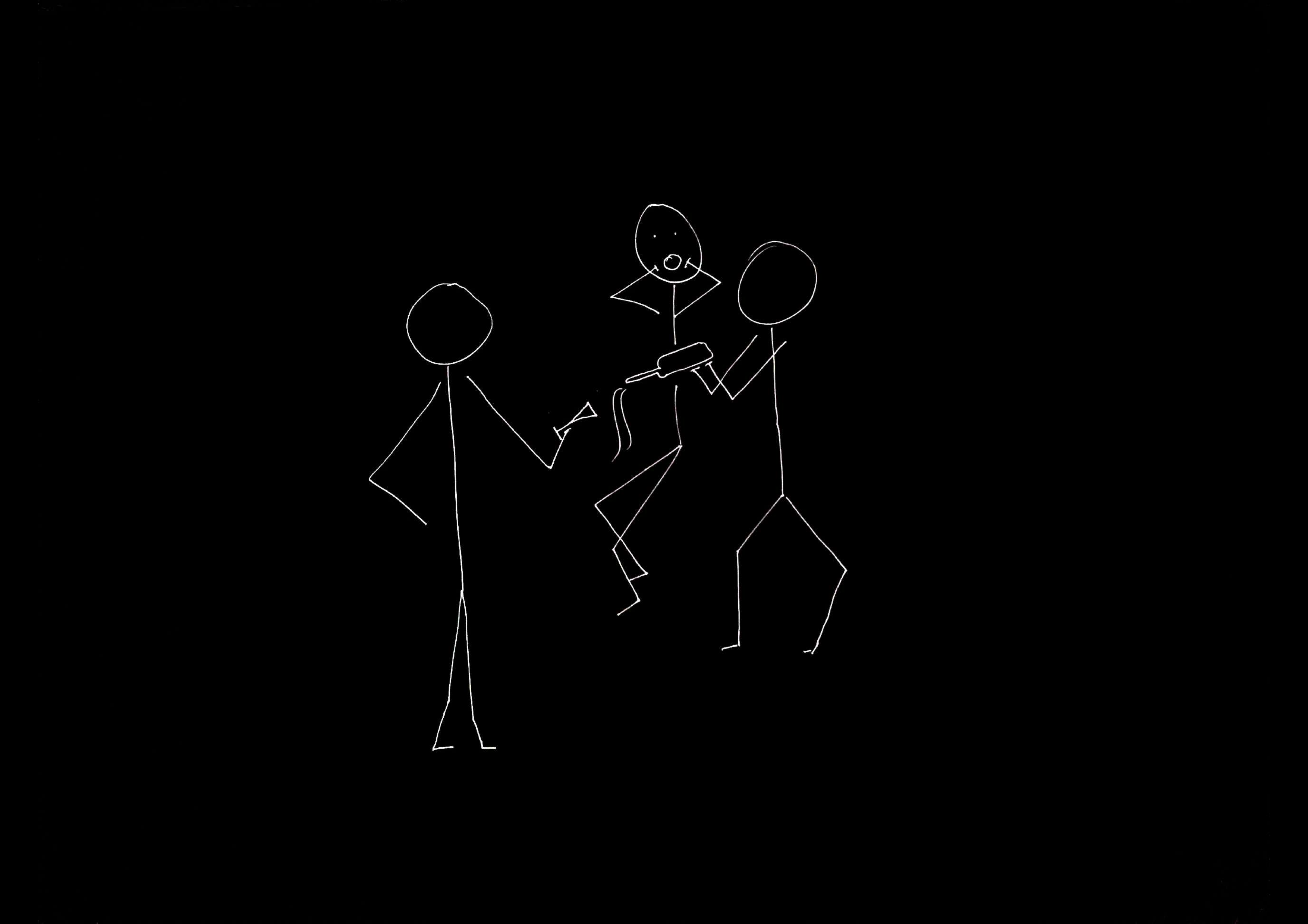

Ayesha takes a glass and holds it up while Beatrice pours prosecco;

unfortunately the prosecco misses the glass and soak Zachs’s trousers.

Here are two sentences, both true:

The tiny drops fell from the bottle.

- distributive

The tiny drops soaked Zach’s trousers.

- collective

The first sentence is naturally read *distributively*; that is, as specifying something

that each drop did individually. Perhaps first drop one fell, then another fell.

But the second sentence is naturally read *collectively*.

No one drop soaked Zach’s trousers; rather the soaking was something that the drops

accomplised together.

If the sentence is true on this reading, the tiny drops' soaking Zach’s trousers is not

a matter of each drop soaking Zach’s trousers.

Now consider an example involving actions and their outcomes:

Their thoughtless actions soaked Zach’s trousers. [causal]

- ambiguous

This sentence can be read in two ways, distributively or collectively.

We can imagine that we are talking about a sequence of actions done

over a period of time, each of which soaked Zach’s trousers.

In this case the outcome, soaking Zach’s trousers, is an outcome of each action.

Alternatively we can imagine several actions which have this outcome collectively---as in

our illustration where Ayesha holds a glass while Beatrice pours.

In this case the outcome, soaking Zach’s trousers, is not necessarily an outcome of any of the

individual actions but it is an outcome of all of them taken together.

That is, it is a collective outcome.

(Here I'm ignoring complications associated with the possibility that some

of the actions collectively soaked Zach’s trousers while others did so distributively.)

Note that there is a genuine ambiguity here.

To see this, ask yourself how many times Zach’s trousers were soaked.

On the distributive reading they were soaked at least as many times as there are actions.

On the collective reading they were not necessarily soaked more than once.

(On the distributive reading there are several outcomes of the same type and each

action has a different token outcome of this type; on the collective reading there is a single token

outcome which is the outcome of two or more actions.)

Conclusion so far: two or more actions involving multiple agents can have outcomes

distributively or collectively.

This is not just a matter of words; there is a difference in the relation between

the actions and the outcome.

Now consider one last sentence:

The goal of their actions was to fill Zach’s glass. [teleological]

Whereas the previous sentence was causal, and so concened an actual outcome of some actions,

this sentence is teleological, and so concerns an outcome to which actions are directed.

- also ambiguous

Like the previous sentence, this sentence has both distributive and collective readings.

On the distributive reading, each of their actions was directed to an outcome,

namely soaking Zach’s trousers. So there were as many attempts on his trousers as there

are actions.

On the collective reading, by contrast, it is not necessary that any of the actions

considered individually was directed to this outcome;

rather the actions were collectively directed to this outcome.

Conclusion so far: two or more actions involving multiple agents can be collectively

directed to an outcome.

Where two or more actions are collectively directed to an outcome, we will say that this

outcome is a *collective goal* of the actions.

Note two things.

First, this definition involves no assumptions about the intentions or other mental states

of the agents. Relatedly, it is the actions rather than the agents which have a collective goal.

Second, a collective goal is just an actual or possible outcome of an action.

An outcome is a \emph{collective goal} of two or more actions involving multiple

agents if it is an outcome to which those actions are collectively directed \citep{butterfill:2016_minimal}.